The scientists used the common bacteria Escherichia coli to produce the genetic material, required to create the modified enzyme (hydrogenase) which strives because it's being protected by the protein shell (capsid) of a bacterial virus (bacteriophage P22). The newly produced biomaterial, the modified enzyme called "P22-Hyd," is said to be 150 times more efficient than the unaltered form of the enzyme. One of its advantages lies in the fact that it can be easily produced at a room temperature via a simple fermentation process.

"Essentially, we've taken a virus's ability to self-assemble myriad genetic building blocks and incorporated a very fragile and sensitive enzyme with the remarkable property of taking in protons and spitting out hydrogen gas," said Trevor Douglas, the Earl Blough Professor of Chemistry in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Chemistry, who also led the study. "The end result is a virus-like particle that behaves the same as a highly sophisticated material that catalyzes the production of hydrogen."

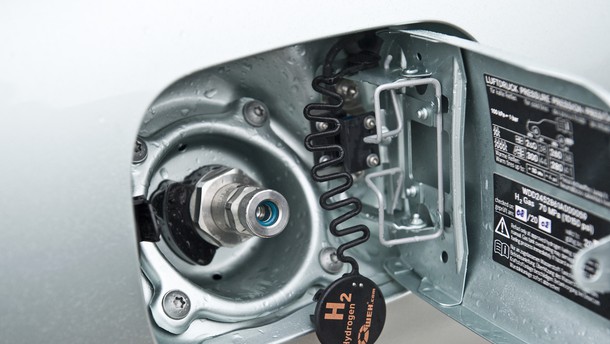

The new material is much cheaper and eco-friendlier to produce than any other material currently used to create fuel cells – for example, platinum, which is both costly and rare, but often used to catalyze hydrogen as fuel in products such as high-end concept cars.

"This material is comparable to platinum, except it's truly renewable," Douglas stated in a press release. "You don't need to mine it; you can create it at room temperature on a massive scale using fermentation technology; it's biodegradable. It's a very green process to make a very high-end sustainable material."

Additionally, P22-Hyd is able to both break the chemical bonds of water to create hydrogen and, on the other hand, to work in reverse to recombine hydrogen and oxygen to generate power. According to Douglas, the reaction runs both ways, so it can be used either as a hydrogen production catalyst or as a fuel cell catalyst.